A two week holiday in Shetland had just about everything I could ask for from a trip within the British Isles: spectacular wildlife on the ground, in the air and out at sea, distant views over stunning scenery, and human history around every corner. Having a longing to spend time on islands, a liking for ferries and a fasciation for abandoned villages, as well as a constant struggle to keep my mind from wandering to nature, Shetland, could just have been the perfect holiday location for me.

I’ve long been wanting to visit Shetland. Ever since starting an odyssey of Scottish Islands 16 years ago, this most northerly archipelago has been calling to me. After having travelled to so many of the Inner and Outer Hebrides as well as it’s southern neighbours in Orkney, Shetland was the last of the major groups of Scottish islands I had to visit. So, after planning the trip for well over a year, and trying to contain my excitement for just as long, we travelled up to these most northerly of the British Isles for a mid-summer holiday in June 2025.

I have to say, it’s not the easiest of places to get to, or, at least, not the quickest, especially if travelling by car; but all good things come to those who wait (or travel far). To be honest, a love a good long road trip, so the drive to Shetland was never going to be an issue. As we made our way up from the East Midlands, we had an overnight stay in Cumbria before a leisurely drive up and across to Aberdeen to catch the overnight ferry to Lerwick, Shetland’s capital. The Northlink ferry identical twins, Hjaltland and Hrossey, are comfortable ships for the 12-hour crossing, particularly if you pay for a cabin. We spent a good while up on deck watching the Scottish land mass disappear and looking out for seabirds and marine life. While waiting for the ferry, we had earlier seen a large pod of dolphins hunting in mouth of Aberdeen Harbour, but sadly didn’t see them again from the ship.

By the time dinner had been eaten and we had a final look out over the sea, it very quickly reached bed time. The cabins are quite a cosy places to spend the night and, fortunately, the blinds in our cabin were good enough to black out most of the very light night sky, as it tends to be in June. It is also a very quick get up in the morning; with the ship docking at 7:00am, there is time for a fast breakfast and a wander up on deck as the ship passes the southern tip at Sumburgh and travels up the long, thin southern spine of the Shetland Mainland. Unfortunately, we didn’t get good views on the way into the port at Lerwick as low cloud shrouded the islands and we had only brief glimpses of the landscapes we were to become very familiar with. As we left the ferry behind us, in good hobbit-style we had second breakfast at a very good cafe (Fjarå) towards the southern end of Lerwick before heading off to our first base for our holiday.

The holiday really began as we boarded the ship but our Shetland experience started properly as we drove out of Lerwick in search of our cottage out on the western side of Mainland. For the first five nights we stayed at a fantastic modern cottage the far side of Walls. Westshore is very smart, clean, comfortable and well-equipped rental property with a contemporary style and great big windows giving wide panoramic views over a wide sweep of sea lochs and low rolling pastureland. The cottage is accessed by a rocky and slightly winding track between two gates, often dotted with dozing ewes and their lambs. The mixture of landscape, sea, wildlife and those sheep, gave a constantly shifting world outside the windows of the cottage which I could have happily sat and watched for hours on end.

After being welcomed by the owner, we unloaded our heavily-laden car and unpacked, looked at the scenery for a little while and then headed the 35 minutes back to Lerwick for a wander and to purchase provisions.

Our first couple of journeys highlighted two things which we were to remark on throughout our stay. Firstly, just how good the roads are; so much of the islands are covered by fast single carriageway (i.e. a lane in each direction) and there’s barely a pothole to be found. As you get to some of the further reaches of the islands, where roads provide access to a few smaller communities, they do narrow down to single track roads (one lane with passing places), but even in summer (we travelled just before the schools finished), there isn’t much traffic to meet on these roads.

The second thing we noted was that the weather can change from one part of the islands to another. As we travelled between our first accommodation and Lerwick, one side of the Mainland was bright and sunny while the other was under dark, dampening skies. It is around 15 miles between where we were staying at Walls and Lerwick, as the crow flies, but more like 25 miles by road. This is not far off the widest part of Mainland, which gives a good distance for the weather to change its mind. Heading between the two places, the roads meet two pronounced moorland-covered ridges, with the valley of Weisdale between (more on Weisdale later). This change in height may contribute to the differences in weather with these ridges being some of the first hills that the wind from the Atlantic meets, creating cloud as the air rises; we certainly saw this happening when we were further down to the south of Mainland. This increase in height also provides opportunities to see great distances (when the weather allows() down the spine of Shetland: at good spots on these ridges you can park at the side of the road and see the islands laid out in front of you towards the south.

Our wander around Lerwick took us through the old town, including coming across the Shetland Pride march, and down to the harbour, where a German sail training ship had docked and was attracting significant attention. Also docked were two cruise ships of different scales, the like of which we would see a few of with our subsequent stops in the capital. Despite some of the cruise ships being enormous, we didn’t come across too many of their passengers, especially away from Lerwick itself, and they never impacted on our holiday.

That afternoon, we also went to the Shetland Museum, located a little way to the north of the town centre; it’s great and gave us a very good introduction to culture and history of the islands, which we were to explore more of over the course of the next two weeks. Readers of my blog may have seen previous posts about visiting villages that had been emptied of their communities as a result of the Highland Clearances. The museum provided some detailed context to the longer history both before and after that period but also details of what life would have been like for communities during that particularly harsh period in the islands’ history. What we saw in the museum was brought to life in our travels around many parts of the islands and in particular by the ancient standing stones, the viking remains and the almost unbelievable number of abandoned houses and communities that we came across. Over the course of the trip we also visited smaller museums at Eshaness and on Unst and Fetlar; while not as polished as their larger, Lerwick counterpart, these were well worth a visit to learn more about Shetland’s past.

As we eventually drove back west for our first night in the cottage, we started to become familiar with the landscapes we would travel through over the next two weeks. There is no ‘typical’ landscape in the islands around Scotland but Shetland has similarities to many of those I have visited before, particularly its nearest large neighbour, Orkney. They share a landscape of low rolling coastal pastureland, dotted with crofts and smaller clusters of homes in hamlets and larger villages. Shetland, however, has far more of the rugged upland moor, with large areas of Mainland, Yell and Unst given over to this sparser populated, more hilly landscape. The deeply indented coastline provides both rocky high cliffs and lower rolling fields reaching down to the sea, with some stunning sandy beaches, pebbly shorelines and a small harbour almost around each corner. The variation means that the landscape seems to constantly change and in a few minutes you can have gone from the sometimes bleak and stark upland, with its dancing carpets of cotton grass, to the softer, lush green pasture along the coasts.

The first few days were spent travelling around Mainland, visiting the islands of Noss to the east and Papa Stour to the west, taking a trip down to the road-linked islands of Trondra, West Burra and East Burra, to the south of Scalloway, and a long day out to the north west of Mainland including wandering around the spectacular area of Eshaness.

The only real disappointments of the entire trip came in the first two days. Both of our pre-booked boat trips were cancelled due to poor weather. The first was a trip to the sea below the towering seabird cliffs of Noss, an island beyond Bressay to the east of Lerwick, and the second was a night-time trip to Mousa, an island to the south east of Mainland, during which we hoped to see storm petrels coming into the famous broch. Not only were the planned trips cancelled but so too were both of the rearranged trips. We didn’t let the disappointment of the cancelled boat trips dampen our spirits and on the first full day on Shetland we took a trip to walk around Noss instead, and it was perhaps the best day of the entire holiday: more of which I’ll cover in a specific blog post.

The day on Papa Stour was a particular highlight. We left the car at the quayside and took the 40 minute ferry from West Burafirth to the island. On arrival, we set off on foot along the only road, serving the few scattered homes, turned north and crossed the airstrip, and then made our way on a winding route along the west coast. The route is spectacular; like so much of the Shetland coast, this part of Papa Stour is dotted with geos (a narrow, steep-sided inlet), islets, stacks and rock arches. The walk is quite winding as you head in and out of headlands created by the geos and in the strong wind we were careful not to get too close to the edge of the coast. As we reached the northern-most part of the walk we turned onto a track for the return leg and the long-threatened rain began. It was heavy but short-lived; we got drenched but with the return of the sun and the strong wind, most of our clothes were drying by the time we got back to the harbour. Like many of the other harbours where the ferries dock, there was a little terminal building with a waiting room and toilets, as well as hot drinks, souvenirs and tablet (a very nice Scottish fudge-like sweet) paid on an honesty box basis. After making use of the facilities we had a lovely sit in the warm sun in a little sheltered spot to give our legs a rest after the rugged eight mile walk.

I can’t mention an ‘honesty box’ without highlighting the cake fridges of Shetland. We have come across them elsewhere, especially in Harris, but the number and variety of these little unstaffed shops was particularly great in Shetland. We bought cakes, jam and fresh berries from the various ‘cake fridges,’, we stopped at.

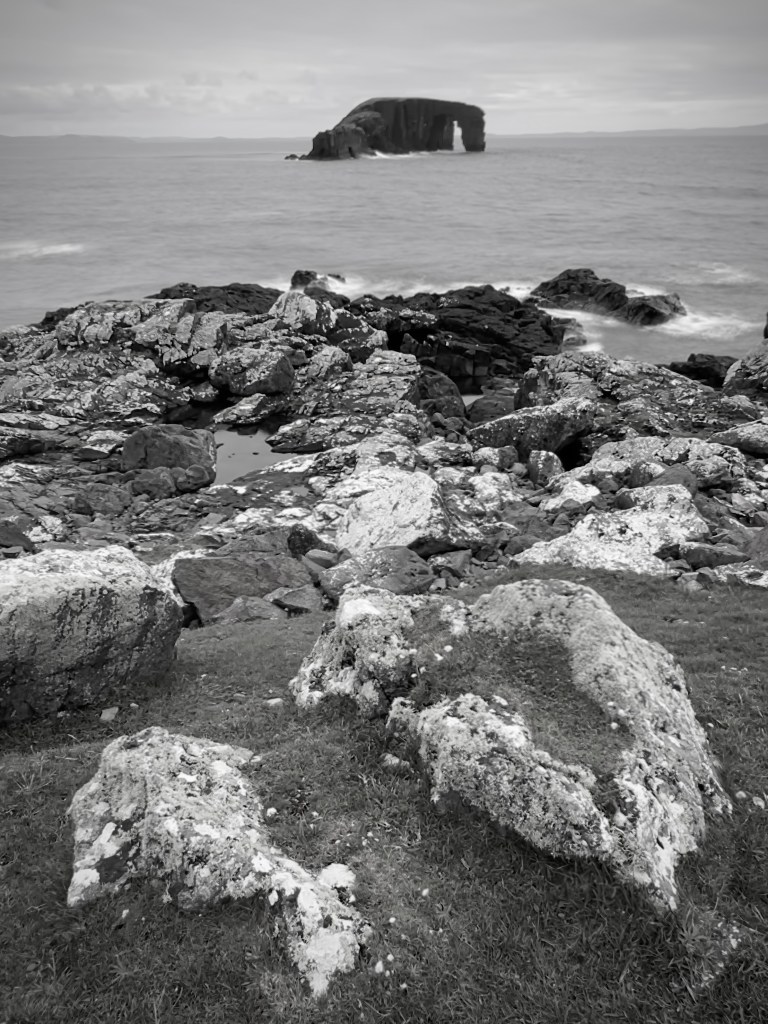

A day spent out on the far north-west of Mainland, eventually stopping at Eshaness was also one to remember. It was another day of grand Shetland coastal landscapes with high cliffs, rocky beaches and off-shore islands. Eshaness itself is worth a wander around once you get to the lighthouse with views that go on for miles, across the green pasture, along the rugged coastline and out to sea. On the way there we stopped at Mavis Grind, a narrow isthmus linking the Mainland to what would be a separate island but for this narrow 90 metre piece of land. It is said you can through a rock between the water on either side, from the Atlantic to the North Sea, but I’m not sure my throwing arm is that good. On the way back we stopped at Stennes Beach to the south to sea Dore Holm, out outlying island with a huge natural arch; we also stopped at Frankie’s Fish & Chips shop, which was great!

Having been to many Scottish Islands at this time of year, we knew that we shouldn’t expect wall-to-wall sunshine and Mediterranean temperatures, and the cancellation of the boat trips is just part and parcel of holidays on the coasts of the UK. However, over the course of the two weeks, the weather we had was probably 40% sunny, 40% cloudy and 20% rainy and, of course, 90% windy. While it was rarely warm when we were out in the open, typically 12 to 14 degrees celsius, the mid-summer sun was strong enough to make it almost hot in sheltered spots. There were actually only a couple of days over the whole two weeks when the rain altered or limited our plans and the wind did get strong enough on one of our trips to Hermaness to make us retreat away from the cliffs to reduce the risk of being blown over the edge. Overall, therefore, the weather was what we expected for a trip this far north.

Our five nights at Westshore were followed by a single night at the Sumburgh Hotel, at the very far south of Mainland. This gave us a chance to visit some of the main sites south of Lerwick including St Ninian’s Isle, Loch Spiggie, the amazing historical site of Jarlshof and, of course, Sumburgh Head itself. We visited the rocky outcrop, with its lighthouse, twice over 24 hours, firstly in the afternoon and then first thing in the morning before breakfast. We went, in particular, in search of close views of puffins and while during the afternoon visit we found comparatively few, the dawn visit presented us with good numbers in the perfect morning light. However, Sumburgh isn’t just all about puffins. This southern-most tip of Mainland has great 360 degree views including out towards Fair Isle, which is visible to the south. There are birds other than puffins too.

The birdlife was one of the main reasons for going to Shetland and weren’t disappointed. Yes, puffins are plentiful and fairly easy to find but so is an array of other birds which make the island a great place to wander around with a pair of binoculars. The seabirds dominate the islands with the cliffs and off-shore islands providing nesting for large numbers. There’s also a large supporting cast of wetland birds, waders and gull as well as the ever menacing skuas and other birds typical of the north in the UK. I’ll do another post to provide more details.

Our final accommodation of the trip was a seven-night stay in a renovated croft cottage on the island of Unst at the very top of Shetland; in fact, it’s the most northerly populated island in the British Isles. After breakfast at Sumburgh, we headed back to Lerwick to replenish our stocks and then took two ferries, first between Mainland and Yell, and then between Yell and Unst.

Car-based travel around Shetland is very easy, with the good roads I’ve already mentioned and frequent ferry crossings on the main routes between Mainland, Yell and Unst. The prices for the ferries are also amazingly cheap, in my view. Prices are £2.80 per passenger for a return ticket, including the ferries to Yell, Bressay, Fetlar and Papa Stour we took. Cars are more expensive, at £16.50 return but even this seems cheap for the longer crossings. What did confuse us at the time was that you don’t seem to pay for the ferry between Yell and Unst. We made that crossing four times (two return trips) and no one ever took payment. On returning home, we checked and it appears that it is indeed a free ferry, possibly to reduce the burden of travel costs for locals.

With the good roads, and frequent ferries on the main routes, it’s also quite quick to get from north to south, especially if you time it right with the ferry crossings. Sumburgh Head in the far south to the ferry crossing to Yell in the north of Mainland is little over an hour while Yell takes around 25 minutes to cross by car, as does Unst. So, allowing for ferries, you can travel the full length of Shetland by car in significantly less than three hours.

The general advice is book the ferry crossings, even for the more frequent routes for Yell and Unst, but definitely for the less frequent crossings, say to Fetlar and Papa Stour. However, we often turned up early for our booked ferry and were waved on by the crews with the ferries having space to spare. The ferries on the main routes, including to Yell, Unst, Fetlar and Bressay are full ‘drive-through’ vessels where you drive forwards both getting on and off them. However, on return from Fetlar, I did have to reverse onto the ferry to enable it to arrive back into Unst pointing in the right direction. To be fair, it wasn’t a difficult manoeuvre, partly helped by there only being three cars on that particular crossing. If the idea of reversing on or off a ferry puts you off, then you might want to leave the car behind if you go to Fetlar or Foula, as you have no choice but to reverse onto that ferry. However, that is largely a moot point as there’s little point in taking the car to those islands if you’re on a day trip.

On reaching Unst, we had a very convenient 10 minute drive to the cottage on the west coast of the island. Like Westshore, the cottage was accessed first by a single track road, then a private track with two gates to pass through. The second gate for was a little fenced corral for the car, and very soon we could see why it was a good thing to park in there. The cottage was in the middle of a sheep field, and while the front and side of the house, as well as the parking space, we inside a fence, the back of the house wasn’t; we got very used to finding lambs standing on the low stone wall at the back, looking into the lounge. I suspect the car would have become a convenient rubbing post for the local sheep without the protection of the fence. The cottage itself was very clean, comfortable and cosy, and had everything we needed for a week’s stay. Being an old croft cottage, like others we have stayed in previously, it has relatively small windows, unlike Westshore the previous week, which meant that, despite arguably having even better views, we didn’t get the benefit of them when inside the cottage.

Our week on Unst, like the previous week, included nature, landscapes and some history with highlights including two trips to the amazing Hermaness nature reserve, day trips to Fetlar and Yell, and a good walk in the south east of the island to some historical sites. Some of these I’ll also write about in separate posts. Highlights also included visiting the most northerly pub and shop in the UK and seeing the site of the first space port being built in the UK (although there isn’t a visitor centre for it, yet).

As long as you don’t mind a long walk out to the cliffs across open moorland (but mostly on a boardwalk), Hermaness is a must for anyone with a liking for seabirds and maritime scenery, and we simply had to go twice! The gannet cliffs are enormous and you can get close enough for some very nice photographs, while being careful not to disturb them or get blown off the top. The nature reserve also provides a sight of the most northerly point of the British Isles, the island of Out Stack, just north of Muckle Flugga with is lighthouse.

A trip to Fetlar is also very much worth it with a chance to find red-necked phalaropes (which we did fleetingly) and yet more lovely scenery. We also had one of the best views of an otter there, with one munching on a massive crab we saw it bring to shore. As I have put in another post, we had some great otter sightings, with Unst being the most productive in our search for them, contrary to the view we had heard that this was the least promising place to look.

During our stay, I spent the quiet evenings reading a book providing a fictionalised account of the Weisdale Evictions; the clearing of communities from villages in that valley between the two ridges dissecting the widest part of Mainland. As I have written on my blog a few times, I find this part of Scottish history fascinating and I’m drawn to the villages abandoned either through the Highland Clearances or later as people found living in these places increasingly impossible. Shetland is covered with abandoned homes and settlements like nowhere else I’ve seen and I simply had to take a walk out to spend time amongst then ruined walls of these deserted communities. We did a walk out to Colverdale on the south-east coast of Unst. Starting at Hannigarth, we walked along Sandwick beach and then on through the Viking history of Framgord and on to Colverdale, with tumbled-down houses scattered across a wide area criss-crossed by field walls and paths. The sense of communities lost was almost tangible under the dark clouds spreading dampness and gloom across the now silent landscape.

After a busy week on Unst, we set off early in the morning to catch the ferry to Yell for the last time, crossed the island and caught the ferry back to the Mainland before driving all the way back to Sumburgh. With the ferry back to Aberdeen not until late afternoon, we had chance for a final bit of puffin watching and then a slow drive up the coast, including a beach walk. The ferry crossing was a little more rough on the way home but not uncomfortably so and despite the gloom we had good views of Fair Isle as we passed it a couple of hours into the crossing and then the coast of Orkney as we stopped there very late into the evening. As we woke the next morning, not long before the ferry docked, the trip came to an end, except for the long seven hour drive back southward.

It took me a long time to write this post; partly because it’s so difficult to sum up those two weeks in just one go. It really deserves far more and I plan, even more than six months later, to write additional posts to ensure I do it, even slightly, some justice.

This was almost without doubt the best trip I’ve had in the UK. That in part was due to having the time over two weeks to spend travelling in a more relaxed way than a single week trip normally allows for. However, the main reason was Shetland itself – it’s spectacular in every way – it is an absolute must for another visit.